Credit: DH Illustration

Stephanie Scanlan learned about the shortages of basic chemotherapy drugs last spring in the most frightening way. Two of the three drugs typically used to treat her rare bone cancer were too scarce. She would have to go forward without them.

Scanlan, 56, the manager of a busy state office in Tallahassee, Florida, had sought the drugs for months as the cancer spread from her wrist to her rib to her spine. By summer, it was clear that her left wrist and hand would need to be amputated.

“I’m scared to death,” she said as she faced the surgery. “This is America. Why are we having to choose who we save?”

The disruption this year in supplies of key chemotherapy drugs has confirmed the worst fears of patients—and of the broader health system—because some people with aggressive cancers have been unable to get the treatment they need.

Those medications and hundreds of other generic drugs, including amoxicillin to treat infections and fentanyl to quell pain during surgery, remain in short supply. But the deepening crisis has not fostered solutions to improve the delivery of generic drugs, which make up 90% of prescriptions in the US.

Robert Califf, commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, has outlined changes the agency could make to improve the situation. But he said the root of the problem “is due to economic factors that we don’t control.”

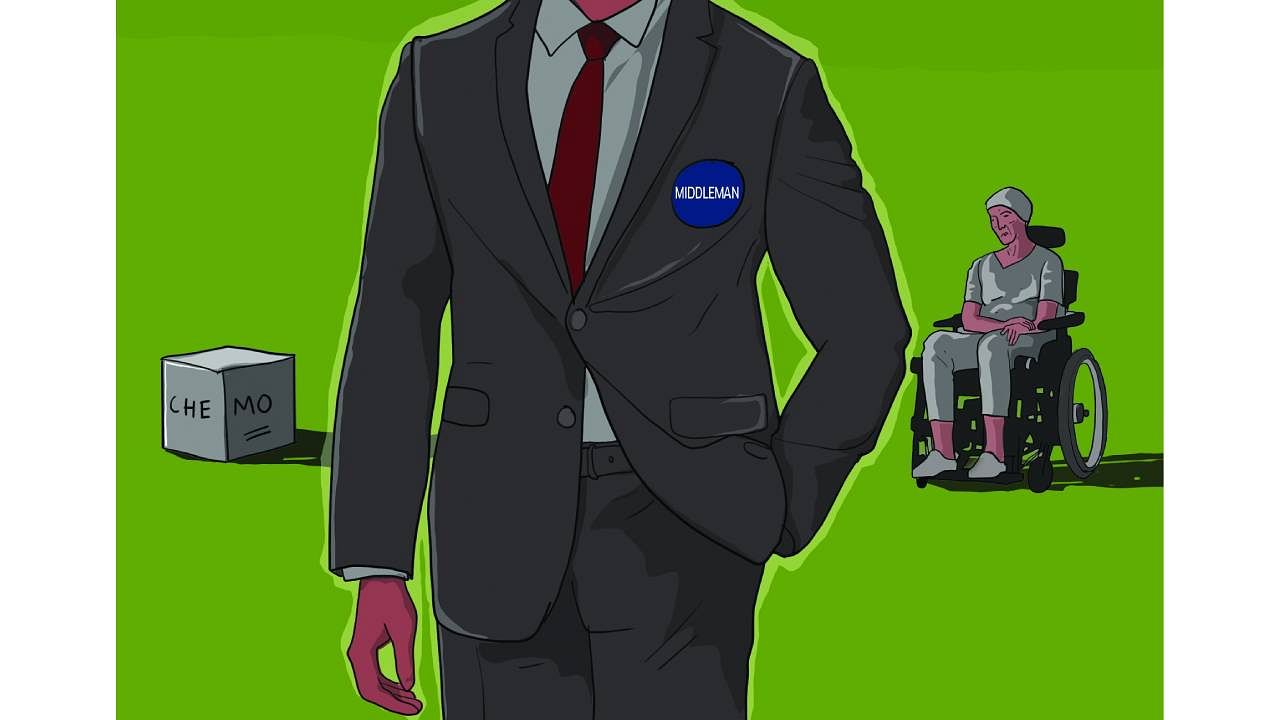

“They’re beyond the remit of the FDA,” he said. Sen Ron Wyden (D-Oregon), chair of the Finance Committee, agreed. “A substantial portion of these market failures are driven by the consolidation of generic drug purchasing among a small group of very powerful health care middlemen,” he said at a hearing this month.

In interviews, more than a dozen current and former executives affiliated with the generic drug industry described many risks that discourage a company from increasing production that might ease the shortages.

They said prices were pushed so low that making lifesaving medicines could result in bankruptcy. It’s a system in which more than 200 generic drugmakers compete for contracts with three middleman companies that guard the door to a vast number of customers.

In some cases, generic drugmakers offer rock-bottom prices to edge out rivals for coveted deals. In other instances, the intermediaries — called group-purchasing organisations — demand lower prices days after signing a contract with a drugmaker.

The downward pressure on prices — no doubt often a boon to the pocketbooks of patients and taxpayers — is intense. The group purchasers compete against one another to offer hospitals the lowest-priced products, which intermediary companies say also benefits consumers. They earn fees from drugmakers based on the amount of medication the hospitals buy.

“The business model is broken,” said George Zorich, a pharmacist and retired generic drug industry executive. “It’s great for GPOs. Not great for drug manufacturers, not great for patients in some cases.”

In a speech to drug supply intermediaries last month, Califf exhorted them to “pay more,” saying it would enhance access to medical products and would be “good for business.”

Prices fell in recent years for two of the three drugs that Scanlan was initially offered to treat her cancer. During those years, Intas Pharmaceuticals, a generics giant in India, steadily gained market share as other companies left, according to data from the US Pharmacopeia, a nonprofit that tracks drug shortages.

But the company had to halt US production to deal with quality issues that the FDA cited after a surprise inspection of one of its sprawling plants in India. Inspectors had discovered quality-control staff workers shredding and throwing acid on key records. The manufacturing shutdown set off a supply shock in February that would be felt nationwide.

Intas recently resumed production, but the FDA still lists the drugs as being in short supply. Major cancer centres report that the shortages are easing, although concerns persist about stock in rural areas.

The scarce drugs are cheap and essential and revolutionised their field decades ago, for the first time curing some patients with testicular, lung, ovarian, pancreatic and breast cancers, oncologists say.

Scanlan’s cancer, called osteosarcoma, was deemed curable for about 65% of patients after cisplatin was added to the cocktail regimen in the 1970s.

Not ‘a First-World Nation’

Dr Julie Gralow, chief medical officer of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, discovered signs of stockpiling in some health systems as early as February when the FDA first announced the shortage, while shelves were empty at other health centers. “We’re calling it a maldistribution based on who has access — who can afford to create a little stockpile at their site,” Gralow said.

The emotional impact has varied widely. Some people with cancer were too focused on paying rent or feeding a family to fight for the medications they desperately needed, said Danielle Saff, a social worker with CancerCare, a nonprofit that supports patients. Others, including Lucia Buttaro, 60, a professor at Fordham University, were furious. She did not get her prescribed carboplatin for a recurrence of ovarian cancer in May or June, even though cancer was spreading in her lungs.

“In my opinion, we don’t qualify as a first-world nation if you can’t get what you need,” she said.

In the case of Scanlan in Florida, because her cancer was rare, invasive and advanced rapidly, it remains unclear whether the shortages played a role.

Still, cancer experts expressed concerns that she had not received standard chemotherapy cocktail regimens before her amputation in September.

Failure to use the three “modern miracle” generic chemotherapies for osteosarcoma patients “is a real problem,” said Dr. Lee Cranmer, a sarcoma expert at Fred Hutch Cancer Center in Seattle, who was not involved in Scanlan’s treatment.

She has since received radiation. Last month, she learned the cancer already in her rib and spine had not spread farther. Although her new care team at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, recently recommended palliative care, she said she felt defeated and terrified.

The shortages took a toll, she said, adding, “I can’t help but think about what if something different happened from the beginning.”