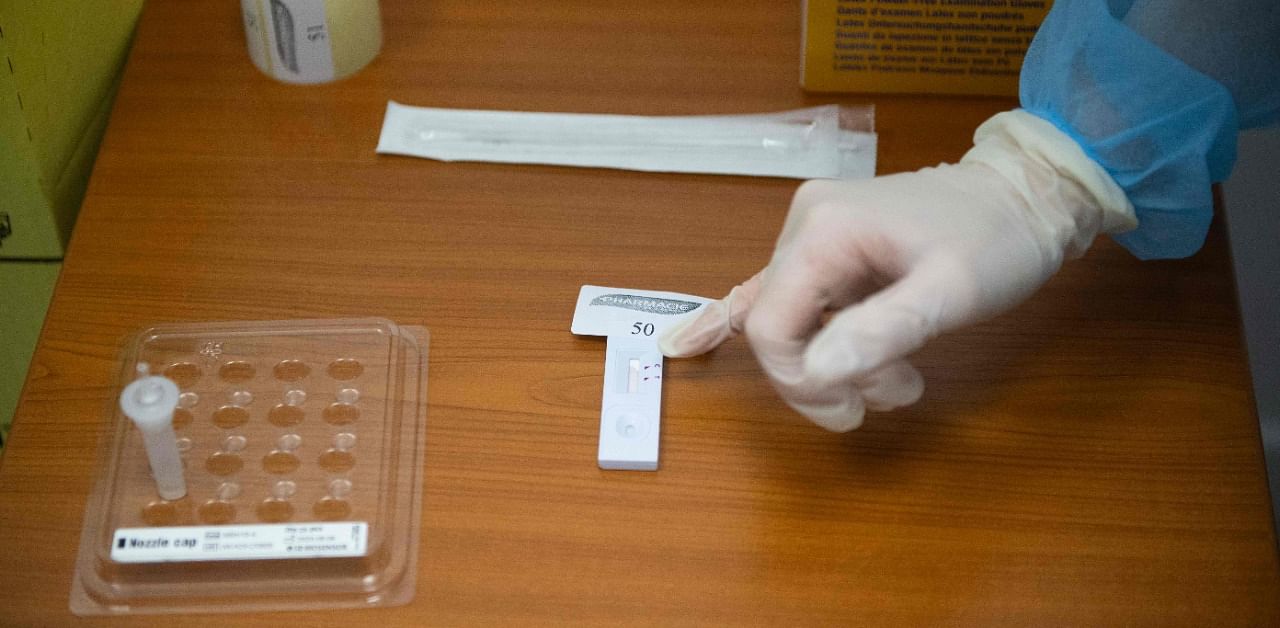

As rapid tests are becoming more widely available, delivering results in minutes in doctor’s offices, nursing homes, schools and even the White House, officials warn of a significant undercount, blurring the spread.

Officials say that antigen tests, which are faster than polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests but less able to detect low levels of the virus, are an important tool for limiting the spread. But they caution that with inconsistent public reporting, the case undercount may worsen.

“We want to be sure that we’re not now saying, ‘there’s no disease,’ when there is lots of disease. All that’s happened is that the science with which we identify it has evolved,” said Janet Hamilton, the executive director of the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, the group that helps the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention define cases of the coronavirus.

Experts say that more rapid testing will lead to more undercounting of cases, even in states that attempt to count them publicly. What’s going on?

— Some states do not count cases based on antigen tests.

Despite CDC guidance to report cases based on PCR and antigen testing, Washington, DC, and seven states don’t publicly share case counts for those with antigen positive tests, including California, New Jersey and Texas.

Another six states keep these tallies separate from their total case counts, and most of these report them less frequently.

The differences among states are due in part to each state’s comfort level with the rapid tests, which aren’t “confirmatory” like PCR tests because they can miss low levels of the virus. Yet most states treat antigen positive cases or “probable” cases the same as “confirmed” cases, by following up with interviews and contact tracing. And a growing number of states, including New Mexico, Oregon and Utah, include individuals with positive antigen tests in their total confirmed case counts.

Individuals who test positive from rapid tests are a small but growing share of all publicly reported cases. For example, in Florida, positive cases from antigen tests make up about 4% of all cases reported since March, the majority of which are based on PCR. But on a daily basis antigen tests contribute a more visible share, making up as much as a third of reported cases in recent days.

These counts are expected to increase as rapid tests purchased by the federal government reach schools and nursing homes across the country this fall.

And cases based on antigen tests can be even more significant in counties where these rapid tests have been more abundant.

For example, at least 26 of 254 Texas counties tally antigen positive cases on local health department websites, and several reveal an increasing dependence on rapid test results. The state Health Department doesn’t yet report these.

In Brown County, in west-central Texas, antigen tests have been widely available since the summer, so the county posts positive cases from rapid tests and from PCR to offer a more complete view of infection, said Lisa Dick, administrator of the Brownwood-Brown County Health Department.

“If we just posted PCR tests we would just be giving the community the idea that things were improving,” said Dick. “And people are making decisions based on that information, from leaders to individuals.”

In Taylor County in rural west Texas, individuals who test positive with rapid tests make up more than half of all cases, as the tests are accessible in the county’s many urgent care centres, said Dr Annie Drachenberg, the medical director for the Abilene-Taylor County Health District.

Patients also tend to prefer the same-day results that antigen tests offer, said Drachenberg, noting that the turnaround time for PCR results peaked at two weeks over the summer before returning to one or two days this fall.

“Once you’ve broken that trust with a patient in terms of getting that answer quickly, it’s hard to get that trust back,” he said.

— Nontraditional testing centres can leave states in the dark.

Whether states publicly report antigen positive cases or just track them internally, many public health officials say their counts are incomplete because they don’t know where rapid testing is taking place in their jurisdictions.

And unlike laboratories that typically perform more complicated PCR tests, many of the “point-of-care” centres doing antigen testing, such as nursing homes, urgent care centres and schools, either don’t realize they need to report lab data, or may rely on slower, less efficient methods such as phone calls and faxes.

“We don’t know for sure what we don’t know,” said Dr Edward Lifshitz, medical director of the Communicable Disease Service at the New Jersey Department of Health, which doesn’t publicly report antigen positive cases because the figure is incomplete.

Lifshitz added that sharing data on antigen positive cases might make some parts of the state, where point-of-care testing centres are reporting correctly, appear worse off than other areas that have missing data.

“It will look like, ‘boy, this part of the state is having an increase in cases,’ when it’s really not,” he said. “It’s just that they are reporting what they are supposed to be reporting.”

To avoid missing antigen test results, some health departments have had to do their own outreach.

In Houston, where infections surged over the summer, health officials searched for rapid testing centres online, made phone calls and posted a “dear provider” letter on their website. In New Jersey, officials have been collecting testing facility names from antigen test manufacturers and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which distributed rapid tests to nursing homes across the state.

But even then, testing centres can still be missed.

Since late September, Alabama has reported three spikes of older cases because point-of-care facilities had neglected to report to public health officials their antigen test results. An urgent care group was responsible for the largest increase, which was reported on October 23, after the addition of older cases nearly tripled the daily count.

Alabama health officials say that as they learn of new testing centres, they are training them to share test data in an electronic format that they can easily work with. Health officials across the country in states like California, Georgia, New Jersey, Oklahoma and Texas, are doing the same, but training can be labour and time intensive, and many testing centres don’t have the technical support they need.

“This is a pipeline that is not well established,” said Kirstin Short, bureau chief of epidemiology at the Houston Health Department.

— Many more tests are on the way.

Scientists who follow the development of coronavirus tests say that rapid testing capacity — most of it antigen-based — could reach 200 million tests a month by early next year, and help the country reach recommended testing levels.

In September the country reported more than 20 million completed PCR tests and about 5 million antigen tests, though the latter is a significant undercount, according to Mara G. Aspinall, a professor of practice in biomedical diagnostics at Arizona State University who tracks Covid-19 testing.

Antigen testing is also expected to grow beyond “point-of-care” tests to include portable kits that individuals can administer themselves. In fact, about two dozen companies are working on these personal rapid tests, according to Aspinall.

Public health officials say these home-based tests, much like a pregnancy test, may be nearly impossible to track. Some experts have also expressed concerns that home-based testing could come with its own set of pitfalls, as large groups of people inexperienced with administering tests use the products and try to interpret their results.

“We may eventually get these tests over the counter,” said Lifshitz of the New Jersey Department of Health. “From a public health perspective that’s a good thing. From a surveillance perspective that becomes a nightmare.”