As a small girl, Trang Nguyen saw a bear stabbed through the chest with a giant needle at her neighbour's house in northern Vietnam.

The bear, flat on its back, was being pumped for its bile, a fluid drawn from its gallbladder that has long been used in traditional medicine to treat liver disease.

"I had seen visitors to Hanoi zoo who brought sticks to poke animals and it really made my blood boil," Trang, the founder of local conservation group WildAct, told AFP.

"But conservation wasn't something I really wanted to do until I witnessed what happened to this bear."

It was the first of her many encounters with a global multi-billion-dollar illegal wildlife trade that devastates species the world over, fuels corruption and threatens human health.

The 31-year-old -- named by the BBC in 2019 as one of the world's most inspiring and influential women -- has spent much of her time since then trying to end the scourge.

She has gone undercover in South Africa to snare traffickers and secured a PhD in traditional medicine's impact on wildlife.

Trang has also set up her home country's first postgraduate course for aspiring conservationists, to help more Vietnamese make it to the top of her field.

In the 1990s, decades of war and isolation meant environmental awareness was a new notion in Vietnam.

Trang recalls her parents telling her: "Only rich people from western countries do that kind of work".

Now there are more local conservationists, wildlife protection laws have been enacted, if patchily enforced, and the number of bears kept in captivity for bile farming has dropped by 90 percent in the last 15 years, according to Education for Nature Vietnam.

But as the country grew richer, demand for exotic wildlife dishes soared and animal parts sought for their perceived health benefits -- such as rhino horn and pangolin scales -- became a status symbol for some within the fast-growing middle classes.

Today the communist country is a key producer, consumer and transit point for trafficked wildlife, says WildAct.

Through courses at Vinh University in central Vietnam and community programmes in wildlife trade hotspots, Trang is trying to empower Vietnamese people to resolve these problems themselves.

In turn, she hopes they will become a louder voice in the global conversation about illegal wildlife trade, and help shape policy.

The responses of some global wildlife organisations to the coronavirus pandemic, widely thought to have begun at a market known to sell wild animals in China's Wuhan, were hugely unhelpful for campaigners in Asia and Africa, says Trang.

One called for a complete ban on "wet markets", even though the term is used in Asia and Africa to describe any market where fresh produce is sold, while another termed them "unhygenic".

"When things like that are said it's very difficult for conservationists to ask people to participate in our work," she explains, as they are seen as "prejudiced".

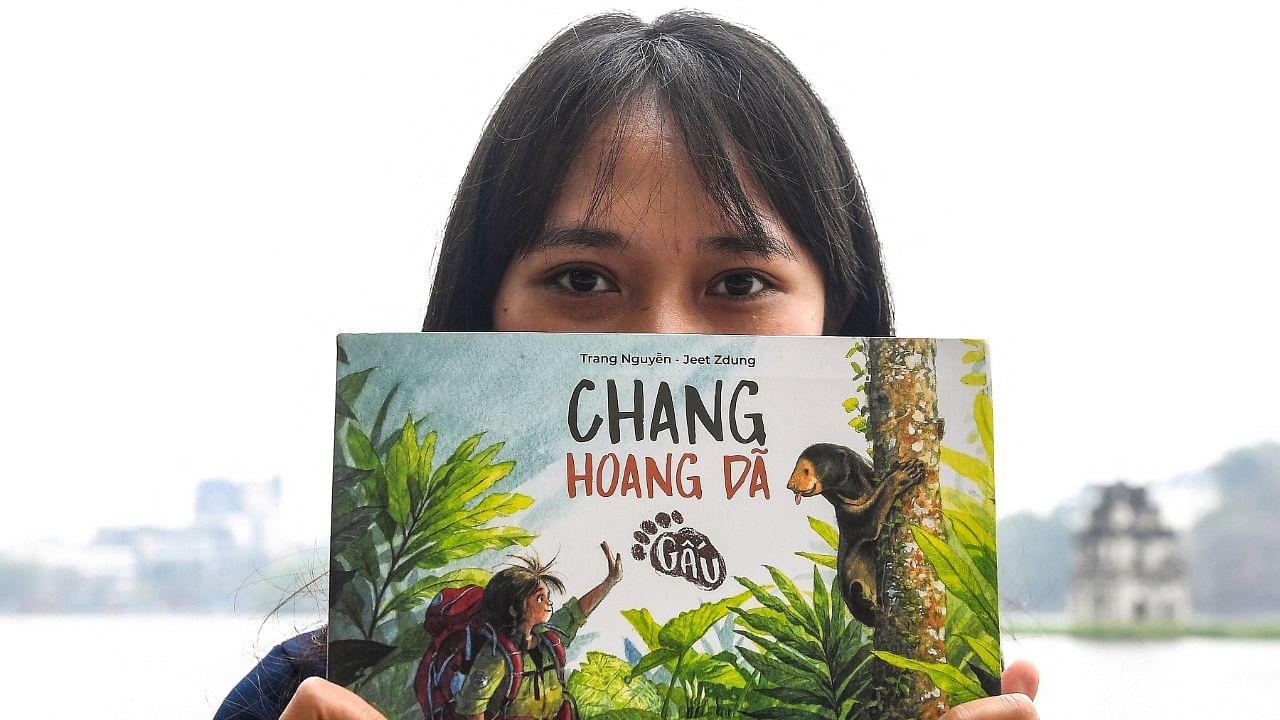

Trang also wants more women in conservation -- a field still dominated by men -- and has written a book to inspire young girls.

Loosely based on her personal story, "Saving Sorya" tells the tale of a Vietnamese conservationist who must prepare a rescued baby sun bear for life in the wild.

Already published in Vietnamese, and due out in English this year, the children's book has a female protagonist -- something she insisted on despite being told "no-one was going to read it" if she did.

Trang's own story is one of remarkable determination.

From the age of eight, she pestered wildlife groups with requests to intern and learnt English by watching the BBC documentary Planet Earth late at night.

She won scholarships to study in Britain, including for a masters degree in conservation leadership at Cambridge University, and founded WildAct in her mid-20s.

Wildlife traffickers are in prison because of her.

"It was very easy for me to pose as a buyer of wildlife products," she remembers of her time working undercover in South Africa.

Around three rhinos are poached there every day, largely for the Vietnamese and Chinese consumer markets, according to wildlife trade monitoring network Traffic.

But it was there that she learnt that the trade is not "black and white".

"One guy I was helping get arrested, he wasn't high up the chain: he was a poor person who got exploited... (and was asked to) to go kill the animal and be the transport."

After the arrest, "I was actually feeling really sad," she said.

"I thought: Now no-one is providing for his kids, they are probably going to become a poacher like him and soon it will be their turn to be imprisoned."

She'll keep fighting for change, she says, but admits it takes a long time to shift people's behaviour.

"For some species, things might not move quick enough to save them."