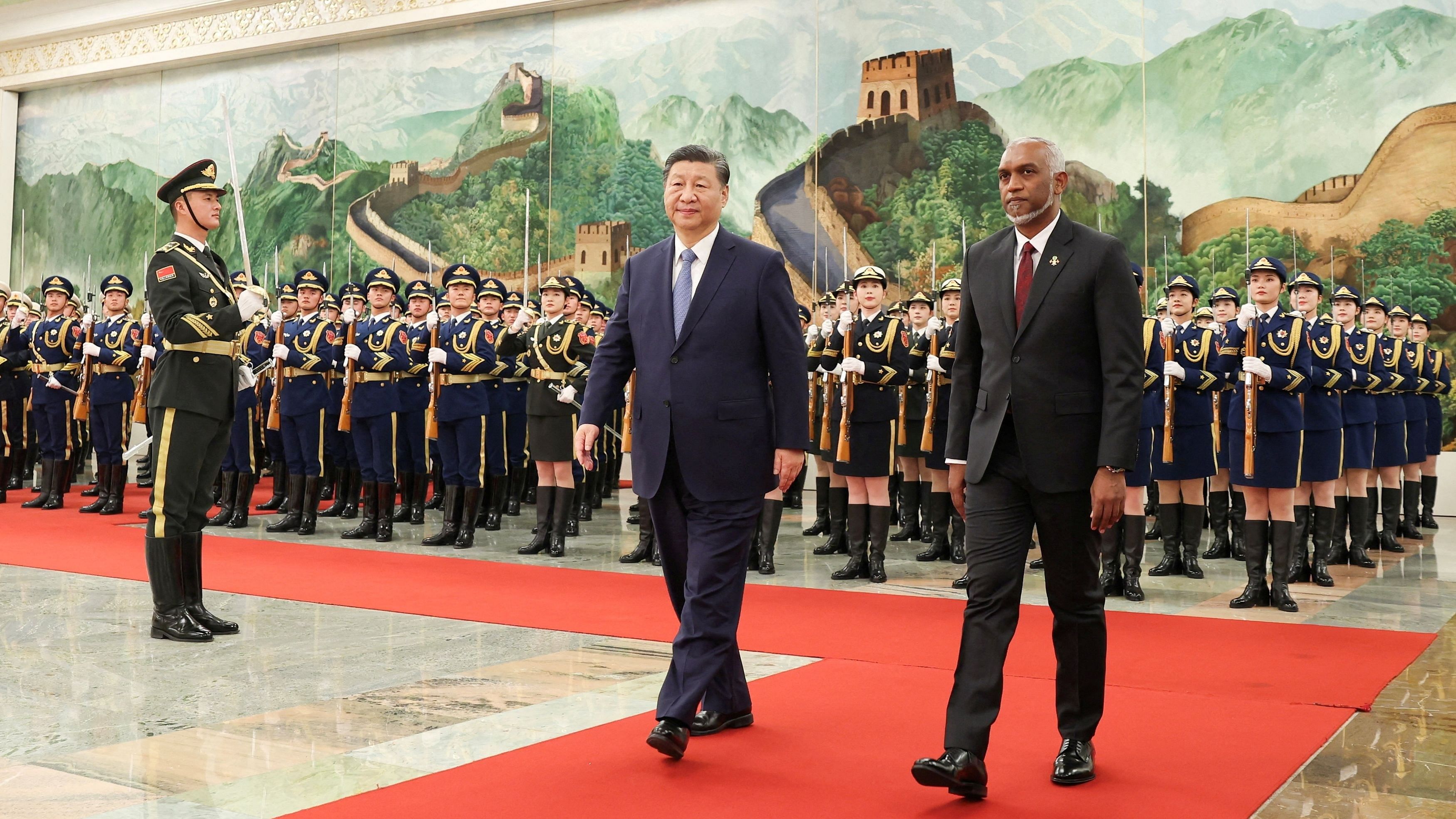

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Maldivian President Mohamed Muizzu at a welcome ceremony in Beijing in January.

Credit: Reuters File Photo

New Delhi: On January 28, Chen Song, Beijing’s envoy to Kathmandu, hosted the representatives of all the political parties of Nepal for a ‘consultation’ with a delegation of the Communist Party of China. The delegation was led by Sun Haiyan, the deputy minister of the International Liaison Department of the Communist Party of China (CPC), who stressed that Beijing wanted good relations not only with the government in Kathmandu but also with the political parties of Nepal. She, however, warned about “some countries”, which did not want the relations between China and Nepal to grow. She asked — not-so-subtly for a change — for Nepal’s political parties not to allow New Delhi or Washington DC to drive a wedge between Kathmandu and Beijing.

Kathmandu was the last destination of the CPC delegation’s visit to South Asia. It started its eight-day tour from Malé in the Maldives on January 22, where Sun called on President Mohamed Muizzu and discussed the implementation of the 20 agreements that China and the Maldives had inked after his recent meeting with President Xi Jinping.

Muizzu took oath on November 17 and immediately started leading the Maldives towards China’s orbit of geopolitical influence — asking India to withdraw its military personnel from the Indian Ocean nation and reversing his predecessor Ibrahim Mohamed Solih’s ‘India First’ policy of treating India as the preferred partner of the nation. It was, however, after Sun’s meeting with Muizzu that Malé announced its decision to accept Beijing’s ‘diplomatic request’ and allow Xiang Yang Hong 3, a “research vessel” of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy, to dock at the main port of the archipelago, disregarding New Delhi’s security concerns.

Sun then visited Dhaka, where she called on Sheikh Hasina and congratulated her for winning a fourth straight term in the office of the prime minister of Bangladesh, even as the United States cast aspersions on the credibility of the recently-held parliamentary elections, which was boycotted by the Opposition parties.

She and her delegation also had meetings with other key functionaries of the ruling Awami League, known for its historic relations with India. She, however, avoided meeting the leaders of the Opposition’s Bangladesh National Party (BNP), which China cultivated for long, before realising that it would not be able to position itself as a potent alternative to the Awami League in the foreseeable future.

The CPC delegation’s recent visits to Malé, Dhaka and Kathmandu are just the latest examples of China’s engagement with leaders and political parties in the neighbourhood of India — the engagement it routinely undertakes every year in pursuit of its strategic objective of expanding its geopolitical influence in the region.

The foundation of the communist country’s global operation to influence political processes and elections in other nations had been laid more than 25 years ago, when its universities started entering into collaborative projects with foreign counterparts, primarily to study how democratic systems work. The network of Confucius Institutes, which spread its tentacles around the world in the past 20 years, has also been put to good use.

China’s bid to influence elections in Canada, the United States and other countries in the West made headlines in international media. So did its bid to interfere in the recent elections in Taiwan.

In South Asia, however, one of China’s recent successes in influencing the domestic politics of another country came in Nepal in October 2017, when it brought the two communist parties, led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal and K P Sharma Oli, together. The alliance forged by Dahal’s Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) or CPN-MC and Oli’s Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist) or CPN-UML not only won the parliamentary elections, but also managed to get the majority in six of the seven provincial Assemblies in December 2017.

Oli took over as the prime minister in 2018 and escalated Nepal’s territorial row with India in 2020, coinciding with the Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s aggressive moves that led to its standoff with the Indian Army in eastern Ladakh. The two communist leaders parted ways in 2021. Oli, however, helped Dahal take over as the prime minister in December 2022, but withdrew support a few months later.

Sun, who was Beijing’s ambassador to Singapore till July 2023, called on Dahal at the official residence of the prime minister in Kathmandu. She also had meetings with Oli and Madhav Nepal, who now heads a third communist party separately. The meetings fuelled speculation about a renewed bid by China to unite the communist parties of Nepal. Several political leaders of Nepal also visited China in the past few months.

Influencing domestic politics

In Colombo, the second of Mahinda Rajapaksa’s two consecutive terms (2005-2015) in the office of the president had seen China expanding its footprints in Sri Lanka and developing strategic assets like Hambantota Port, causing much unease to India. After his brother Gotabaya Rajapaksa took over as the president and Mahinda, himself, became prime minister in 2019, Sri Lanka’s drift towards China resumed, with the CHEC Colombo Port City project gaining momentum. India’s support to help Sri Lanka recover from its economic crisis in 2022 and 2023 helped it claw back the space it had lost to China in the island nation. But Beijing is likely to try again to bring back a regime favourable to it to power in Colombo after the presidential elections in Sri Lanka later this year.

Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth’s government in Mauritius, in recent years, faced repeated protests by opposition parties for undermining national sovereignty by allowing India to build a military base at Agaléga Island and allegedly to install an internet traffic monitoring system at a submarine cable landing station. New Delhi suspects the role of Beijing’s diplomats in Port Louis in orchestrating the clamour against India.

It is, however, in the Maldives that China achieved the greatest success in its bid to influence the domestic political processes in the countries in the vicinity of India. The People’s Party of Maldives (PPM) government, led by Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom, had steered the tiny island nation into a debt trap by awarding the state-owned companies of China contracts to build several infrastructure projects – mostly on unsustainable loan terms. Though Beijing’s influence over his regime had resulted in strains in New Delhi’s relations with Malé, it saw a reset after Solih and former Maldives President Mohamed Nasheed led the Maldivian Democratic Party to victory in the November 2018 elections. Beijing was, of course, not amused with Solih’s ‘India First’ policy and Yameen soon launched an ‘India Out’ campaign. Muizzu was among the ones on the frontline of the ‘India Out’ campaign, which New Delhi suspected to be a joint project of China and Pakistan. The campaign gained momentum over the years and helped Muizzu beat Solih in the presidential elections in September 2023.

China is likely to keep seeking political influence in the countries around India even as it continues to develop strategic assets across South Asia and the larger Indian Ocean region. How should New Delhi respond? “Politics is politics. I cannot guarantee that in every country, every day, everybody will support us or agree with us,” External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar recently said in response to a query on the strained ties between New Delhi and Muizzu’s government in Malé. “Politics may go up and down but the people of that nation generally have good feelings towards India and understand the importance of having good relations,” he added, perhaps indicating how New Delhi could deal with the challenges posed by the changes in the political environment, not only in the Maldives but for that matter in any neighbouring nation.