A day after striking a deal in principle with President Joe Biden to raise the debt limit, Speaker Kevin McCarthy and his leadership team began an all-out sales pitch on Sunday to rally Republicans behind a compromise that was drawing intense resistance from the hard right.

To get the legislation through a fractious and closely divided Congress, McCarthy and top Democratic leaders must cobble together a coalition of Republicans and Democrats in the House and the Senate willing to back it. Members of the ultraconservative House Freedom Caucus have already declared war on the plan, which they say fails to impose meaningful spending cuts, and warned that they would seek to block it.

So after spending late nights and early mornings in recent days in feverish negotiations to strike the deal, proponents have turned their energies to ensuring it can pass in time to avert a default now projected on June 5.

Also Read | US debt ceiling deal: The key takeaways

“This is the most conservative spending package in my service in Congress, and this is my 10th term,” Representative Patrick T McHenry, R-NC, a lead member of McCarthy’s negotiating team, said at a news conference on Capitol Hill on Sunday morning.

House Republicans circulated a one-page memo with 10 talking points about the conservative benefits of the deal, which was still being finalized and written into legislative text on Sunday, hours before it was expected to be released. The GOP memo asserted that the plan would cap government spending at 1 per cent annually for six years — although the measure is only binding for two years — and noted that it would impose stricter work requirements for Americans receiving government benefits, cut $400 million from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for global health funding and eliminate funding for hiring new IRS agents in 2023.

“It doesn’t get everything everybody wanted,” McCarthy told reporters on Capitol Hill. “But, in divided government, that’s where we end up. I think it’s a very positive bill.”

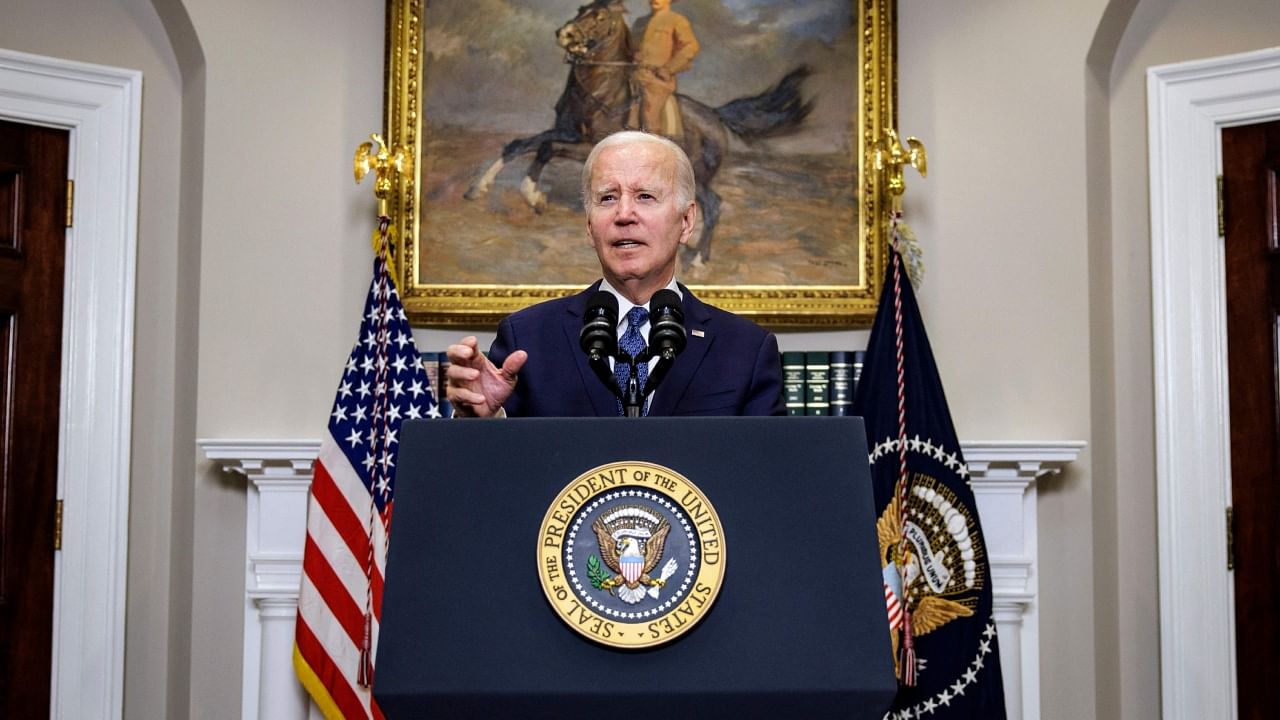

Biden told reporters that he was confident the deal would reach his desk and that he spoke with McCarthy on Sunday afternoon “to make sure all the T’s are crossed and the I’s are dotted.”

“The agreement prevents the worst possible crisis, a default for the first time in our nation’s history,” Biden said later in the day, adding, “It also protects key priorities and accomplishments and values that congressional Democrats and I have fought long and hard for.”

Biden said it was an open question whether the deal would make it through Congress. “I have no idea whether he has the votes,” he said of McCarthy. “I expect he does.”

Still, the deal, which would raise the debt ceiling for two years while cutting and capping some federal programs over the same period, was facing harsh criticism from the wings of both political parties.

“Terrible policy, absolutely terrible policy,” Representative Pramila Jayapal, D-Washington, said on CNN’s State of the Union, referring to the work requirements for food stamps and other public benefit programs. “I told the president that directly when he called me last week on Wednesday that this is saying to poor people and people who are in need that we don’t trust them.”

Jayapal, the chairperson of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, said she wanted to read the bill before she decided whether to support it.

Some on the right had already ruled out doing so before seeing the details.

“No one claiming to be a conservative could justify a YES vote,” Representative Bob Good, R-Va, a member of the House Freedom Caucus, wrote on Twitter. Rep. Dan Bishop, R-NC, posted his reaction to news of the deal: a vomit emoji.

Russell T Vought, former President Donald Trump’s influential former budget director who now runs the Center for Renewing America, encouraged right-wing Republicans to use their seats on the House Rules Committee — which McCarthy granted them as he toiled to win their votes to become speaker — to block the deal. “Conservatives should fight it with all their might,” he said.

Some Senate Republicans, who under that chamber’s rules have more tools to slow consideration of legislation, were also up in arms.

“No real cuts to see here,” Senator Rand Paul, R-Ky, said on Twitter. “Conservatives have been sold out once again!”

“With Republicans like these, who needs Democrats?” asked Senator Mike Lee, R-Utah, who has vowed to delay the debt limit deal.

Senator Lindsey Graham, R-SC, was also critical — although for a much different reason. He called the deal too stingy, demanding more robust military funding, particularly for the Navy.

“I am not going to do a deal that marginally reduces the number of IRS agents in the future at the expense of sinking the Navy,” Graham said on Fox News Sunday.

But McCarthy argued that Republican critics were a small faction.

“More than 95 per cent of all those in the conference were very excited,” McCarthy, who briefed Republicans about the deal on Saturday night, said on Fox. “Think about this: We finally were able to cut spending. We’re the first Congress to vote for cutting spending year over year.”

The deal would essentially freeze federal spending that had been on track to grow, excluding military and veterans programs.

Representative Dusty Johnson, R-SD, an ally of McCarthy’s, said that House Republicans would overwhelmingly support the debt deal. He played down the right-wing revolt, claiming that leaders never expected certain House Freedom Caucus members to vote for it.

“When you’re saying that conservatives have concerns, it is really the most colourful conservatives,” Johnson said on “State of the Union,” pointing out that some Republicans even voted against a more conservative proposal to raise the debt ceiling. “Some of those guys you mentioned didn’t vote for the thing when it was kind of a Republican wish list.”

Still, it was clear McCarthy would need votes from Democrats to pass the measure through the House — and those might not prove easy to deliver, especially from the left wing in the House.

Representative Jim Himes, D-Conn, said he was undecided about how to vote but expressed anger at the negotiations, which he compared to hostage-taking on the part of Republicans.

“None of the things in the bill are Democratic priorities,” Himes said on Fox. Himes said the legislation was not “going to make any Democrats happy.”

“But it’s a small enough bill that in the service of actually not destroying the economy this week may get Democratic votes,” he said.

Representative Hakeem Jeffries of New York, the House minority leader, said on CBS’ Face the Nation that he expected that “there will be Democratic support once we have the ability to actually be fully briefed by the White House.”

But he was clear that he did not like the position Democrats were in.

“We have to, of course, avoid a market crash. We have to avoid tanking the economy. We have to avoid a default,” Jeffries said. “The reason why we’re in this situation from the very beginning is that extreme MAGA Republicans made the determination that they were going to use the possibility of default to hold the economy and everyday Americans hostage.”