Less than four months before the US election, President Donald Trump has made his tough China policy a centerpiece of his campaign to stay in power.

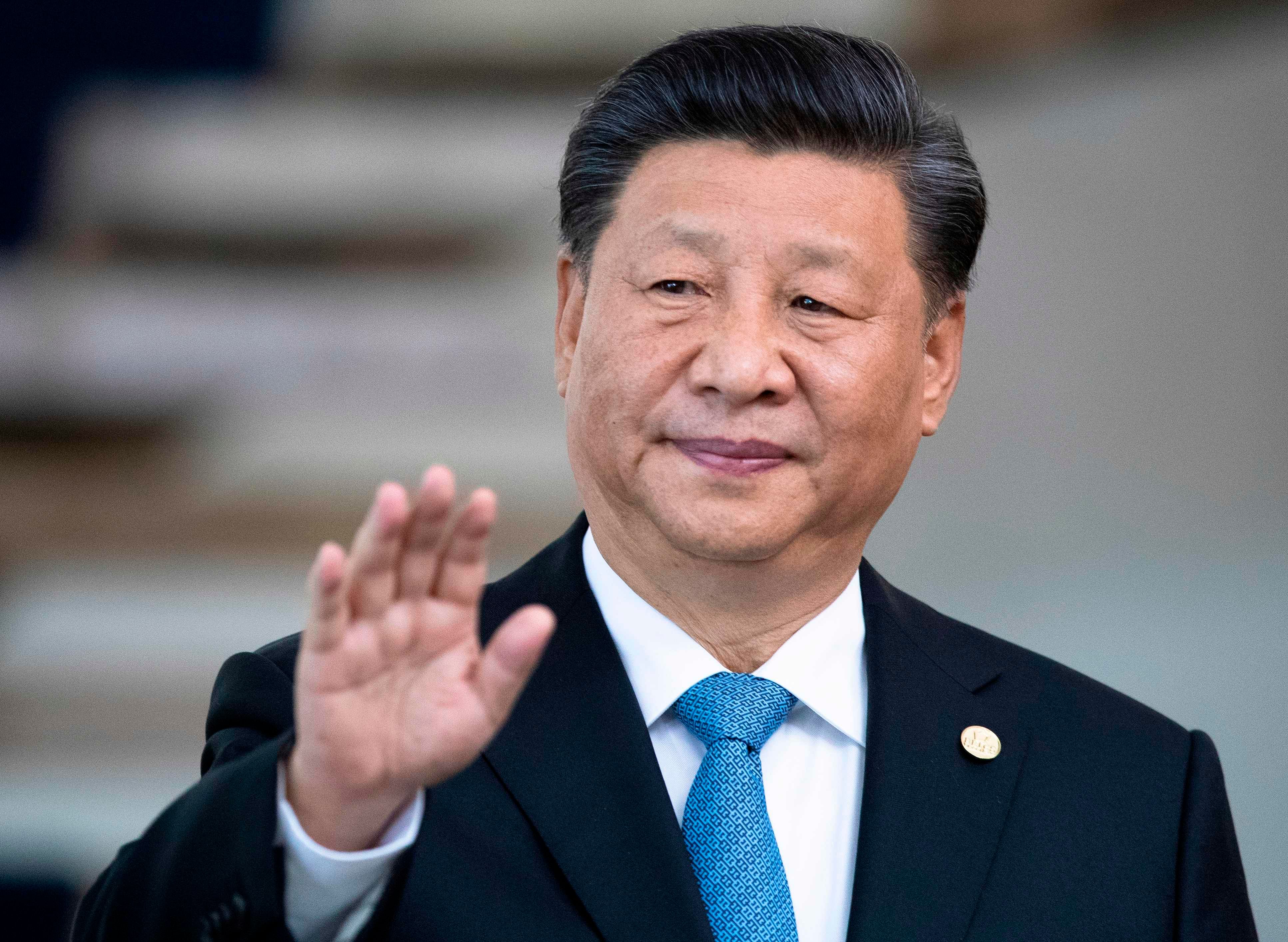

Over in Beijing, President Xi Jinping is similarly preparing for China’s own leadership contest in 2022. While the country’s 1.4 billion citizens don’t get a vote, public sentiment still matters when it comes to how much support Xi can muster from senior Communist Party leaders for his indefinite rule.

A crucial pillar of that support has been Xi’s personification of standing “tall and firm” in the world, an image he’s brandished by strongly asserting claims in the South China Sea, spending billions to upgrade military hardware and tightening Beijing’s grip over Hong Kong. While that’s generated nationalism that has buoyed his support, helping make Xi the country’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong, it’s also set China on a collision course with the rest of the world.

China has “almost created a dynamic where it has to be externally assertive in order for the party to maintain control domestically, so there’s almost a kind of impulse of clashing with the interests, values and sensitivities of other countries,” said Rory Medcalf, a professor at the Australian National University who wrote “Indo-Pacific Empire: China, America and the Contest for the World’s Pivotal Region.”

“It’s almost as if the way Xi Jinping has rewired the Chinese system, it can’t help it -- it can’t help itself,” he added. “That is obviously very damaging for China’s interests in the long run. It’s actually very damaging for all of us.”

‘Real Resistance’

The deterioration of US-China ties -- the closure of the Houston consulate was the latest in a long string of tit-for-tat action -- is just the tip of the iceberg. In recent months, more countries have spoken out against Chinese actions in places like Hong Kong and Xinjiang. And China’s diplomats, eager to please party leaders, have sparred with countries ranging from the U.K. and Australia to India and Kazakhstan.

A new purge with the Communist Party ranks may explain why officials are so eager to demonstrate their loyalty. Quishi Journal, the party’s official magazine, published excerpts from Xi’s speeches this month saying the party leadership should be embodied in “every aspect and every link” of society. An accompanying editorial called Xi the “ultimate arbiter.”

“His campaign to remain in power at the 20th Party Congress has definitely started,” said Susan Shirk, chair of the 21st Century China Center at the University of California, San Diego. “There is very likely some real resistance under the surface in the system, and 2022 will be very interesting. I don’t think it’s a slam dunk.”

The biggest question looming over Chinese politics is when Xi, 67, will step aside after breaking with succession practices set up after Mao’s fraught tenure. He has pledged to transform China into a leading global power by 2050, with a thriving middle class, strong military and clean environment.

In recent weeks, Xi has sought to weed out dissent among China’s security forces. The Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission, the party body that oversees the country’s police, prosecutors and courts, announced an “education and rectification” campaign to “thoroughly remove tumors” from the justice system. Its top official compared the campaign -- set to last through 2022, when Xi’s term as party leader expires -- with a political purge that consolidated Mao’s paramount position more than 75 years ago.

Xi also placed the People’s Liberation Army reserve forces under direct control of the central government and Central Military Commission, changing a rule whereby they reported to both the PLA and local government. And he took steps to silence critics of his government’s response to the pandemic while attaching top priority to “safeguarding the regime’s security.”

Perfect Storm

While China’s citizens aren’t going to rebel against Xi, a “perfect storm” scenario in which a Covid-19 upsurge forces another lockdown, Chinese stocks crash and countries pressure companies to withdraw investments could lead to splits in the leadership, according to Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies. That’s dangerous for Xi, he said, because of the precedent he set by jailing former security chief Zhou Yongkang after he retired from the Politburo Standing Committee, China’s most powerful body.

“He knows that he’s got a lot of enemies, and the enemies are not dissidents,” Tsang said. “The enemies are within the top echelon in the Communist Party.”

Right now there’s no reason to think Xi is facing any imminent threats. While his government’s initial handling of the pandemic generated widespread dissatisfaction, Xi’s subsequent ability to reduce cases and restart economic activity helped mitigate the damage -- and compared positively with the responses of countries like the US, where the virus is still running rampant.

China’s economy has also continued to expand, even if growth rates weren’t as impressive as during his predecessor’s watch. Economic data released in July suggest the country is back on the path to recovery, even though the figures showed worrying trends such as a decline in retail sales and a drop in investment by private companies. Xi this week urged companies to innovate and pledged to further open the economy, saying China will “stand on the correct side of history.”

“His position is much more secure than any time before largely because of his success, from the Chinese perspective, in containing coronavirus,” said Cheng Li, director of the Brookings Institution’s John L. Thornton China Center. “We should not underestimate his capacity and his popularity.”

Disputes Surging

Although gauging public opinion in China is always difficult due to strict censorship, a Harvard University study released this month showed that satisfaction rates among Chinese citizens in 2016 had increased markedly across all levels of government compared with 2003, with officials seen as “as more capable and effective than ever before.” It found that citizens respond positively and negatively to measurable changes in their well-being, which could be a “double-edged sword.”

“While the CCP is seemingly under no imminent threat of popular upheaval, it cannot take the support of its people for granted,” it said.

Without democratic elections, the Communist Party’s roughly 200-member Central Committee nominally elects the party leader and lawmakers pick the president -- titles both held by Xi. In reality, leadership positions are hashed out behind the scenes among various factions, a process that starts several years before the Party Congress and remains largely a black box to outsiders.

Whereas a decade ago it was possible to see the government as a separate entity, under Xi the party has become paramount, said Rana Mitter, director of the University of Oxford China Center. That has contributed to a surge in border disputes flaring up at the same time, he said, as promoting nationalism has become more important than creating new diplomatic links.

“In a way that would be less necessary in more prosperous times,” Mitter said.

Xi’s consolidation of power has made him at once more secure and more vulnerable, with any missteps like the initial response to Covid-19 providing an opening for any rivals to pounce, said Tsang from SOAS University of London. On the world stage, he said, Xi’s administration is “picking fights with everybody.”

“When you’re running it as a strongman, you really cannot afford to show any signs of weakness,” Tsang said. “And this is what we have with Xi Jinping.”